The Misfortune Teller

You Can't Do A Wrong Thing The Right Way

The distant Trojans never injured me." -- Homer, The Illiad

"I ain't got nothing against no Viet Cong." -- Muhammad Ali (refusing conscription into the Army in 1967)

Memoirs of a Misfit

Every story has to start somewhere

[Internet photo]

[Internet photo]

According to my service records, I reported to Travis Air Force Base (San Francisco Bay Area) on June 30, 1970. I seem to remember sleeping overnight in a vast transit barracks before departing on a Flying Tigers Airline flight, first to Anchorage Alaska, then to Yokoda Airbase in Japan, and then to Tan Son Nhut Airport in Saigon, South Vietnam. I don't remember how many days that took, but according to my paperwork, I had orders to check in to the Plaza BEQ (Bachelor's Enlisted Quarters) on July 7th. I spent three days -- it seemed more like a month -- in that stinking toilet of a "hotel" before flying north to my assigned duty station at the Vietnamese Naval Training Center at Cam Ranh Bay on July 10th as relief for a departing seaman. I spent the next three months there with essentially nothing to do, so out of boredom I decided to grow a moustache and beard. Admiral Elmo Zumwalt, the Chief of Naval Operations, had issued fleet-wide orders saying that we enlisted men could do that to improve our morale. But my local commanding officer did not like my morale and ordered me to shave off the offensive (to him) facial hair. I respectfully declined, reasoning: "What can they do to punish me? Send me to Vietnam?" I soon discovered the answer to that rhetorical question when my commanding officer had me transferred to the most remote ATSB that he could find: "Solid Anchor," essentially a pile of sand dumped on a defoliated stretch of mud on the banks of a dirty brown salt-water river about two kilometers from the southernmost tip of Vietnam. As irony would have it, Solid Anchor owed its very existence to none other than Admiral Elmo Zumwalt, who had ordered the facility built when he previously commanded all U.S. Navy forces in Vietnam. I arrived at Solid Anchor in early November, 1970, and stayed until the end of January, 1972, a period of about fourteen months. I had a long time in which to ponder the irony of my situation -- and much else besides.

Actually, this story starts a year earlier, when I received the following set of orders

DATE: JULY 09, 1969

TO: COMMANDING OFFICER

NAVAL NUCLEAR POWER TRAINING UNIT

PO BOX 2751

IDAHO FALLS, IDAHO 83401.

BUPERS TC B1889. TRF JUL 69 EM2 MICHAEL R. MURRY, USN, B81 75 63 TO RPT NET 0001, 20 AUG 69 BUT NLT 1500, 21 AUG 69 TO CO NAVPHIBASE CORONADO FOR 7 WKS TEDUINS COI (4 WKS ACADEMIC PHASE AND 3 WKS SERE) COMPTEMDUINS AND WHEN DIRECTED BY CO NAVPHIBASE FFT TO RPT NET 001, 17 OCT 69 BUT NLT 1500, 18 OCT 69 TO SUPT NAVPGSCOL MONTEREY FOR DUINS 32 WKS WITH DEFENSE LANGUAGE INSTITUTE WEST COAST BRANCH COI VIETNAMESE LANGUAGE (CRS NO. O4VS32KO470) CLCVN 20 20 OCT 69/ENDING 18 JUN 70. COMPLY OPNAVINST 11101.20 CIC 2NCG05197563. FOR CHNAVADVGRP MACV: ULTIMATE ASSIGN TO CHNAVADVGRP MACV AS AN ELECTRICAL ADVISOR PARA/LINE N14/14.

Translation from military gobbledegook into plain English:

Electricians Mate Second Class Michael R, Murry will transfer from the Naval Nuclear Power Training Unit in Idaho Falls, Idaho, and report no later than 1500 (three o'clock in the afternoon) on the 21st of August 1969 to the commanding officer of the Naval Amphibious Base, Coronado Island (near San Diego) for seven weeks of temporary duty instruction (4 weeks academic phase and 3 weeks Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape (SERE)) at the conclusion of which he will report no later than 1500 on the 18th of October 1969 to the Superintendent Naval Postgraduate School Monterey for 32 weeks of duty instruction with the Defense Language Institute West Coast Branch in the Vietnamese Language (Southern Dialect), course beginning on 20 October, 1969 and ending 18 June, 1970. In compliance with Operational Naval Instructions he will ultimately be assigned to the Chief of Naval Advisory Group, Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, for duty as an Electrical Advisor.

First the seven weeks of "Counter-Insurgency" training

[Internet photo]

[Internet photo]

The seven weeks of training at the Naval Amphibious School at Coronado Island, San Diego, started out pretty well. Since we didn't have enough time at the facility to warrant getting stationed there, we got Temporary Attached Duty (TAD) status, which meant that the Navy issued us some money for short-term housing. So another E-5 student and I chipped in to rent an apartment together in nearby Mission Bay. Not bad.

The first month -- the academic (classroom) phase -- went quickly. It seems that I remember reading Street Without Joy, By Bernard Fall (about the French experience in Indochina) but, if so, it only served to reinforce my already bad attitude about anything to do with Vietnam. Apparently, we had already lost the war sometime back in my freshman year of high school (1961-1962). Good to know this seven years later with two more years of my life scheduled to waste losing some more. Mostly we just read from prepared military materials and heard lectures on Vietnamese culture, military organization, economy, etc. All of it had something to do with "winning the hearts and minds" of the Vietnamese. If I remember correctly, the standard military translation of that policy went something like, "Grab 'em by the balls and their hearts and minds will follow."

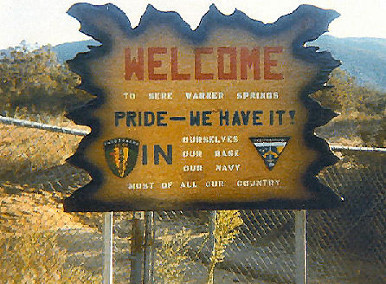

The last three weeks royally sucked. First, we had to head out to Camp Pendleton for a week or so of weapons training with the Marines. The gunnery sergeant instructors had a lot of fun with us sailors. Before every demonstration of the right way to use a machine gun, hand-grenade, or mortar round, they would ask for a volunteer to show everyone "how John Wayne would do it." Nobody volunteered. On one occasion, the marines put us through a gas-mask exercise in a closed compartment like you might find on a ship. Once inside, they told us to take off the masks and sing the Marine Corps Hymn before they would let us out. Naturally we refused and did a lot of choking since most of us Navy men didn't even know the damn song. After that, we had to endure a week of SERE (Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape) training out in the scrub brush and desert at nearby Warner Springs. Many days and nights spent marching around in the dirty dust, up and down hills, with hardly anything to eat except a bite of an apple and a little water once in a while. After we got so weak that we could barely stand up without fainting, we got thrown into a little POW camp for a day-and-night, just to show us what we could expect should the "Viet Cong" ever capture us. Then back to the main base at Coronado -- starving, dirty and unshaven -- for some real Navy chow. We all filled our plates with piles of food, only to discover that our stomachs had shrunk so much that we could barely eat more than a few bites before feeling "stuffed." FTN.

Then the thirty-two weeks of Vietnamese Language training at DLIWC

[Internet photos]

[Internet photos]

Although I reported to the Naval Postgraduate School, I actually stayed in an old WWII-style barracks and did my studying at the Presidio of Monterey, an Army base overlooking the bay and Fort Ord off in the distance.

We had classes six hours a day, five days a week, for eight months. The school employed the Aural/Oral (Listen First, Speak Later) method of instruction. We had issued to us a tape player (about the size of a small suitcase) and tape recordings of the lessons we would have to learn. Each night we had to memorize the strange noises on the tapes until we could approximately reproduce them ourselves. Then, for three hours each morning in class, we would break down the memorized noises into Vietnamese words and sentences, i.e., "dialogs," somewhat reflective of real-life situations. After lunch, we would spend three hours having introduced to us -- with one hour in the language laboratory -- the next day's noises which we would memorize that night, and so on day after day until we had become somewhat proficient in "Monterey Dialect," which our instructors assured us, no one spoke anywhere in Vietnam. But you've got to start somewhere.

Except for the few times when I had duty of some kind, I could drive home on weekends to Orange County, Southern California, a distance of "only" about 365 miles. I (mostly) grew up in Garden Grove, but my mom and step-dad had a house in Westminster (now better known locally as "Little Saigon"). Once home I could visit with my folks and friends (mostly of the female variety). I could leave school in Monterey on Friday afternoon, cut over to Salinas and then down Hwy 101 to San Louis Obispo for a refueling. I would continue south on 101 through the Santa Maria Valley down to Santa Barbara and (for the last leg of the journey) through Ventura County and Los Angeles till I got home. I could usually make the trip in about six-and-a-half hours in my little Volkswagen fastback. On the return trip, I would leave mom's house just before Sunday midnight and pull into the Presidio of Monterey just in time to change into my uniform, have "breakfast" (or what passes for that in Army chow halls), and then settle in for my first class of the day -- a very long day. I did this almost every weekend for thirty-two weeks. After awhile, I could fall asleep at the wheel but the car knew how to stay in its own lane and when to pull into San Louis Obispo for more gas. One night passing through Passo Robles ("Robber's Pass," in Spanish), a can of shaving cream on the floor in front of the back seat exploded from the heater and rudely awakened me. I don't know how I did all that driving for all those lonely hours. But I did.

Soon enough, the day came when I graduated from Defense Language School, West Coast Branch, and reported to Travis Air Force Base as instructed for transfer to Southeast Asia and whatever awaited me there.

Passing through Saigon and "Chinatown," naturally

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

I passed through Saigon about nine times over the course of eighteen months. Initially, I flew into the city upon arrival "in-country" for transfer to my first duty station at Cam Ranh Bay. Upon transfer from Cam Ranh Bay to ATSB Solid Anchor, I passed through again. On three separate trips abroad for scheduled R-and-R (namely, a week in Hong Kong, a month in Japan, and a week in Taipei, Taiwan) I passed through Saigon a total of six more times (going and coming back). Finally, I passed through Saigon one last time on my way out of that corrupt and pitiful excuse for a "country." So, yes. I passed through Saigon nine times, usually for only a few days each visit.

It didn't take me long to find a better place to stay than that stinking Plaza BEQ (Bachelor Enlisted Quarters) transit toilet. Early on in my extended tour I found this little "full service" hotel in Cho Lon, or "Chinatown." Better food. Better looking women. And the "mama-san" who ran the place took good care of me, especially since I used to bring her little presents whenever I would hit town. One time, I happened to look out the back window of my room down onto this back alley where a Chinese man in his shorts and t-shirt sat reading his Chinese newspaper while his two sons washed and polished this classic Ford 1955 Thunderbird hard-top convertible. All that U.S. aid money pouring into Saigon had to go somewhere, I suppose.

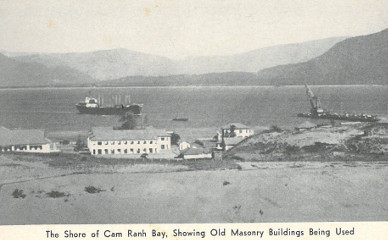

Cam Ranh Bay as it looked in 1966: four years before I got there

[Internet photo from TME Looks Back: Vietnam - "Army Engineers in Vietnam" and "Operations at Cam Ranh Bay,"

February 29, 2016, by Stephen Karl]

[Internet photo from TME Looks Back: Vietnam - "Army Engineers in Vietnam" and "Operations at Cam Ranh Bay,"

February 29, 2016, by Stephen Karl]

Cam Ranh Bay had changed a great deal from 1966 until I got there in July of 1970. Even so, our small Naval Advisory Group attached to the Vietnamese Naval Training Center had quarters in one of these old, two story cement buildings probably left over from when the French ran things. The one we stayed in still had those slow-moving ceiling fans that barely stirred the hot air up above below. As an Electrician's Mate, I had no Vietnamese counterparts to work with, but occasionally I got to do some DIY wiring for our own convenience: things like power outlets for lighting, fans, refrigerators, etc.

Pilot's last day in Vietnam

[Internet photo]

[Internet photo]

I made several trips down to Solid Anchor flying on the USAF Carribou C-7 (or C7-A) because it could take off from, or land on, very short runways such as Solid Anchor's perforated metal airstrip. The big plane had a ramp in the rear and cargo netting draped along the insides of the fuselage. On one memorable trip, we took off without first raising the ramp, so we passengers could look out the back of the plane and see that we had barely cleared tree-top elevation. We flew along like that for some time, watching water buffalo scatter in panic beneath us as we came roaring overhead, when the pilot's voice came back to us over the intercom. He sounded a bit inebriated and very happy as he informed us: "This is my last day in Vietnam and I don't give a fuck." Just about then we heard a sound like gravel rocks bouncing off the outer skin of the ship. The pilot immediately put the plane into a nearly vertical climb as we desperately hung onto the cargo netting, suddenly looking down out of the still open rear ramp as it gradually began to close. Once safely at a higher altitude and with the rear ramp secured, the pilot levelled off and we flew for quite awhile without incident. When the pilot figured he had flown about as far in the right direction as he should have, his voice came back once more over the intercom: "Does anybody know the call sign of this place where we're going?" Lucky for us (I suppose), one of the guys seated near me -- a radioman -- did know Solid Anchor's frequency and call sign so we got the instructions we needed to visually identify or destination and home in for a landing.

From Cam Ranh Bay to Solid Anchor: the Air Force Drops me off

[Internet photo]

[Internet photo]

I don't remember which airport we flew out of on our way down to Solid Anchor. We could have flown straight from Saigon or else from Binh Thuy Army/Air Force Base, the military airport furthest south and closest to Solid Anchor. I do remember the plane, however: the "Carribou" (C-7). Hard to forget something like that. It had two mammoth engines, an elevated tail assembly, and a rear loading ramp for vehicles and such. As an STOL (Short Take Off and Landing) aircraft, it could climb or drop almost vertically before levelling off at the last minute and landing on (or taking off from) very short runways of the kind that the SeaBees (Navy Construction Battalions) had built at Solid Anchor using a "Marston Mat" (also known as pierced (or perforated) steel planking (PSP)). Once the wheels hit the ground, the pilot would throw those two huge engines into reverse which would bring the big plane to a rather rapid stop.

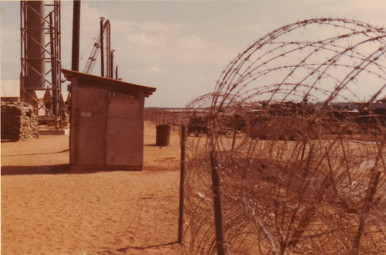

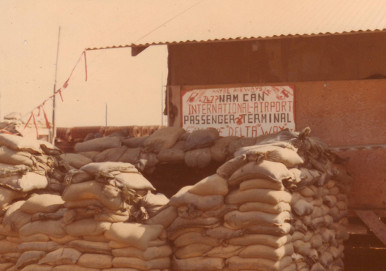

First Look at Nam Can International Airport Passenger Terminal

[Photo by Ed Lefebvre, Brown Water Navy: Solid Anchor 1971-1972 web site, PHOTO 203, "Nam Cam International Air Terminal Bunker."]

[Photo by Ed Lefebvre, Brown Water Navy: Solid Anchor 1971-1972 web site, PHOTO 203, "Nam Cam International Air Terminal Bunker."]

I first laid eyes on this humorously labelled "airport infrastructure" in November of 1970, immediately after exiting the Air Force Carribou C-7 in one piece. I felt like I had just survived a dive off a high cliff after that landing! By the time I left Solid Anchor at the end of January, 1972, the bunker didn't look even this good. But by the standards then prevalent in the southern half of Vietnam, it seemed typical.

Floating Repair and Maintenance Barge along with moored assault craft

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

After reporting in to someone in authority (I think, an enlisted E-6 who outranked me) I got assigned to the repair and maintenance shops located on this floating barge not far from where the swift boats and assault craft normally docked. For a few weeks I worked in the sweltering heat and humidity trying to establish some sort of communication with the few Vietnamese sailors who had something to do with small boat electrical systems. In more than four years of duty in the regular navy, I had scarcely ever worked in my Electrician's Mate rating, having made it to E-5 in three years on the basis of taking and passing fleet-wide examinations. Then, after a year of nuclear power training in 1968-1969 I got orders to 7 weeks of Counter-Insurgency School and 32 weeks of Vietnamese language training at DLIWC before deploying to the now-defunct Republic of South Vietnam. Anyway, I did manage to start picking up the language as actually, spoken which ability landed me another job that I kept for the remainder of my time at Solid Anchor.

Assault Craft tied up together near floating repair shops

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

I didn't get to work for long with the other U.S. advisers and their Vietnamese counterparts down in the floating shops doing real work on real boats (which seemed always tied up together like some sort of floating slum). For several weeks, the base had another American interpreter/translator, but he shipped out and the base commander called me in to issue me a change of assignment. Henceforward, I would report to NOC, the base Operations Center, for duty translating radio messages and Vietnamese commendations for awards (medals) as well as doing any general purpose interpreting that the doctor and corpsmen needed me to do in Sick Bay whenever Vietnamese patients needed treatment. In any event, the Ops Center had air-conditioning for the electronics equipment and a heavily sandbagged exterior, so it seemed like an acceptable change of work environment. Mostly, I became the Base Interpreter/Translator Gopher.

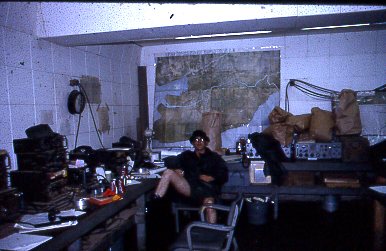

Interior of NOC -- Operations Center

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

Not me, but a radioman on duty in NOC. I had a desk in the Ops Center with a couple of Vietnamese to English and English to Vietnamese dictionaries. I translated messages and other routine communications duties when not out on-call for just about any translating or interpreting that anyone wanted me to do. At times, an officer would go up to the big acetate map on the wall and stick pins in it to mark the coordinates where our little base artillery piece would drop explosive rounds at random times during the night. We called this a "Free-Fire Zone" on the theory that any Vietnamese wandering around out there in his or her own countryside could only mean "enemy activity" of some sort. So if a peasant farmer or fisherman (or their wives or kids) got blown up during the night out taking a pee or a crap (since they had no indoor plumbing or electricity), then they only had it coming to them. Occasionally, on the day following the nightly shelling, some Vietnamese villagers would come in to see our base doctor to have shrapnel removed from various parts of their bodies. Not much choice for them.

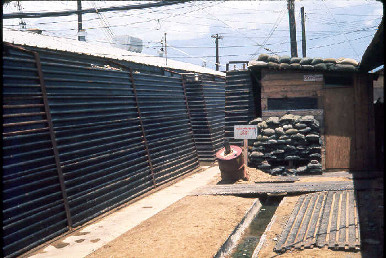

Exterior of NOC -- Operations Center

[Photo by Ed Lefebvre, Brown Water Navy: Solid Anchor 1971-1972 web site, PHOTO 204, "Solid Anchor Operations center."]

[Photo by Ed Lefebvre, Brown Water Navy: Solid Anchor 1971-1972 web site, PHOTO 204, "Solid Anchor Operations center."]

One day in January of 1971, an enlisted member of the local SEAL team came bursting into the Ops Center, all out of breath, to announce that "The Lieutenant is dead." I clearly remember the American base commander walking out of the Ops Center to investigate, with me not far behind. From just outside the front door to NOC we could see four little Vietnamese sailors lifting the American's body out of their boat and up onto the pier. While at Solid Anchor I witnessed several Vietnamese deaths, along with some very serious injuries, but I only saw one American die in Vietnam. Not too many years ago, I finally visited the Vietnam War Memorial in Washington, D.C. and looked up the man's name along with that of a high school classmate of mine. I didn't feel sad, just angry at the needless waste.

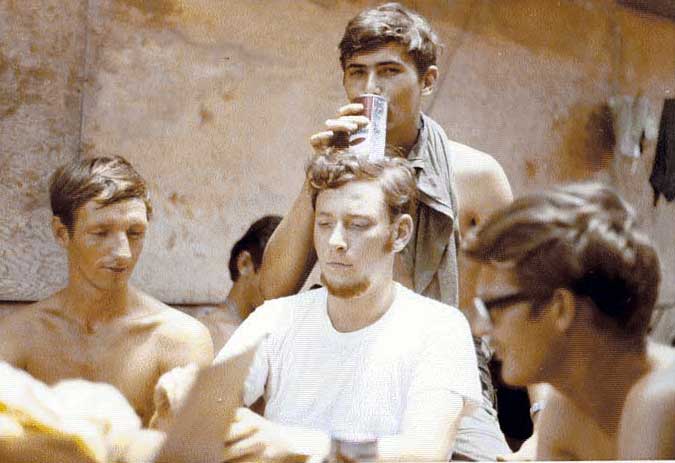

Solid Anchor Foursome

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

Me second from left in my next-to-only pair of pants. The guy to my left with the can of beer used to work as a motorcycle mechanic for Honda of Dallas. Later he got transferred to a pretty cushy billet in Saigon. I ran into him once travelling through town on my way somewhere. He used to tell me stories of working on Japanese motorcycles when a local biker would come in with a chopped Harley Davidson asking to have it fixed. He would tell them: "We have enough work to do on serious motorcycles."

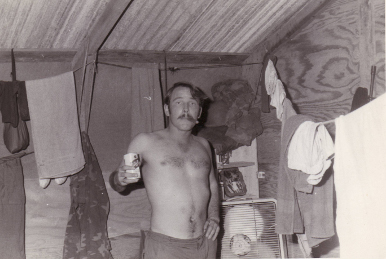

Delux Accomodations

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

I usually showered and shaved (my chin) every couple of days. I also (less frequently) washed my few pairs of shirts and pants and hung them up to "dry" (as far as that can ever happen in the sub-tropics) in my little corner of our little barracks. Still, I had more space than I would have had aboard ship. I had it somewhat better (in terms of personal space) when stationed at the Vietnamese Naval Training Center at Cam Ranh Bay, since we had quarters in a two-story cement building located somewhat away from the other facilities there. But once at Solid Anchor, like everyone else, I just "adjusted" as well as I could. Nothing much I could do about the situation, and in time the abnormal became "normal."

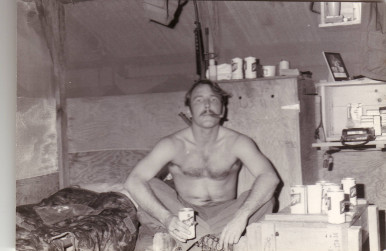

Still plenty of beer and "shipmates" to share it with

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

At the beginning of each month a shipping container full of beer and other necessities of life arrived to help make our existence somewhat bearable. I can't speak for everyone else -- although I think I speak for many -- but we alcohol and nicotine addicts usually drank up the entire supply of beer (I think the cigarettes and cigars lasted somewhat longer) in the first week or so. Naturally, I don't remember much of what happened during those periods of binge drinking, but other people filled me in on the awful details.

Before Exhausting the Monthly Beer Supply

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

Then I went too far with the alcoholism thing. Just before my supply of beer ran out one month during the spring of 1971, I went on a bender one night in the middle of a pouring rain. Someone bet me five dollars that I would not take off all my clothes, put on my steel helmet, and march across the compound to the Ops Center and report for duty with the watch officer. I won the five dollars. I almost wound up in a padded cell.

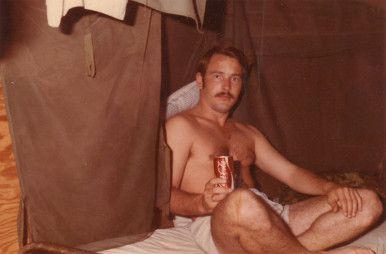

After Sobering Up at the Thought of a "Psych Evaluation"

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

Once I sobered up from my personal "Monsoon Escapade," I got a summons ordering me to report to one of our base officers, I don't remember which one. The man sat me down and explained my "options" going forward. I don't remember his exact words, but he said something like: "Murry, you have a unique job here and you do it well. We would have a difficult time replacing you. But it has become apparent, after that stunt you pulled last night, that you have too much unoccupied time on your hands. You need a hobby. Either you find one, or we may have to send you up to one of the bigger bases up north for a psychiatric evaluation. Which would you prefer?" The thought of a "psych evaluation" scared the living shit out of me, but I had no idea what kind of a hobby I could possibly take up at Solid Anchor, about as remote an outpost as one could find in the southern part of Vietnam. When I asked him what he thought I could do for a hobby, he suggested: "Well, you're a language guy, so why don't you take a correspondence course in some other language, say, Japanese, for example. Any of us officers can sign off on your homework and proctor your exams." It just so happened that I owned a book on Japanese that I had bought from the USO bookstore at Cam Ranh Bay at the suggestion of an older shipmate. "OK," I answered, "I'll do that." So, I sent off for a correspondence course in Japanese from the University of Oklahoma, through USAFI, the U.S. Armed Forces Institute. I even finished the course before leaving Vietnam and received three units of college credit. I didn't know it at the time, but that decision set the direction that much of my life would take thereafter. Thank goodness for Coca Cola addiction as an alternative to alcoholism.

Gag Photo with two friends.

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

Pretty useless equipment for an interpreter/translator, formerly a nuclear power plant electrical operator, surplussed to the southern part of Vietnam (the very most southern part) to help drag out the long retreat until President Richard Nixon could win re-election at the end of the following year without becoming "the first U.S. President to lose a war." Life in the Fig Leaf Contingent, Brown Water Navy branch.

Two Raggedy-ass Radiomen Shipmates.

[Photo by Mike Turner]

[Photo by Mike Turner]

RM2 Mike Turner and [I think] RM3 Rich Long.

Showers and fork-lift pallets.

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

We didn't have to travel far from our barracks in order to take a shower, but we had to watch our step around all those fork-lift pallets littering the ground in every direction. They had a purpose: namely, to give us something to walk on when the torrential rains turned the sand into mud. Unfortunately, and especially at night, a person could break a toe or leg tripping over those things in the dark. Also, in those showers lurked a particularly nasty species of big black fly who just loved to take a bite out of a human ass at every opportunity. So, the trick to getting clean without also getting bit lay in how fast one could make it from the barracks to the shower and back with just a towel wrapped around the lower extremities. Taking the time to dress and undress again while in the shower building just gave the fly more time to score a meal.

Outdoor Head, the ubiquitous Barbed Wire, and Perimeter Tower

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

Narrative text pending.

Back from a trip to the Can.

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

Narrative text pending.

Morning Excrement Disposal Detail.

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

Ah, the smell of burning shit in the morning.

Barracks "Hooches" with Sandbag Bunkers

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

Narrative text pending.

*** 30-Day Basket Leave in Japan, July 1971 ***

About a month before the end of my normal one-year tour of duty in Vietnam (July 1970 through June 1971), my supervising officer at Solid Anchor asked me to consider extending my tour for an additional six months. He had anticipated my possible negative reaction to this suggestion by pointing out several facts that might influence my decision. First, he pointed out that after completing my year "in country" I would have thirteen months left on my six-year enlistment. Navy policy at that time required that anyone returning from Vietnam with more than a year left on their enlistment would have to serve out every day of it at a new assignment. However, those returning to the U.S. with less than a year remaining on their enlistment would get an early discharge, which in my case meant six months less to do in the Navy. Second, if I elected to leave Vietnam and return to the regular Navy, I would not receive overseas pay and combat pay, nor would my savings receive the ten percent tax-free interest that they did in Vietnam. In other words, I would have to do another thirteen months of the (relatively worse) poverty that I had experienced my first three years in the Navy. Not an attractive prospect. Third, and to sweeten the incentive for me to extend my tour in Vietnam, the Navy would offer me a month basket leave, anywhere in the world, which would not count against my regular yearly one-month leave allowance which I could sell back to the government upon leaving military service. Plus, I would get an additional one-week R-and-R in either Australia, Hong Kong, Bangkok Thailand, or Taipei Taiwan. I had already been to Hong Kong on my first R-and-R, but that still left me with acceptable alternatives. Since I wanted to get out of the Navy in time to resume college at the earliest date (early February, 1972), I filled out the papers and extended my tour of Vietnam for six additional months "at the request and for the convenience of the government." Since I had started studying Japanese to keep from going insane at Solid Anchor, I chose to spend a month in Japan.

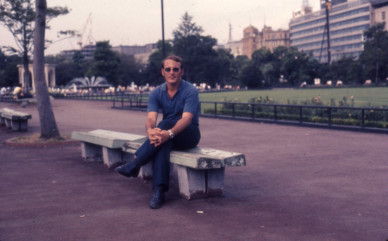

Me at Hibya Park, Tokyo, Japan (July, 1971)

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

I flew into Japan and arrived at Yokoda Air Base outside Tokyo. I had one thousand dollars in my pocket and no idea where to go. I followed a pair of sailors out the front gate of the base and over to a train station where they bought tickets to Yokohama. So I bought a ticket to Yokohama, too. But when we got off the train in Yokohama, I lost them, and so I decided to get a room at the first nearby hotel. When I saw the price of the room and breakfast, I quickly calculated that I would go broke in less than a month unless I found someplace much cheaper to stay. So I asked where I might find such inexpensive lodgings (some sort of "hostel" frequented by students and poor travellers) and went there the next day to check in. Then I had to find the cheapest food that I could subsist on given my limited budget. I settled on little bits of barbequed chicken on a stick (Yakitori) and buckwheat noodles (Soba). I lost twenty-five pounds that month in Japan, considering all the walking around I did to save transportation costs, but I made it on my limited funds and learned a great deal about Japan and its people in the process.

Me at Hayama Beach, south of Yokohama, Japan (July, 1971)

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

My new friend at Hayama Beach, south of Yokohama, Japan (July, 1971)

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

Narrative Pending.

*** Back from Civilization in Japan ***

Primitive Sunday Entertainment at Solid Anchor.

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

During my fourteen months spent languishing at "Solid Anchor," a shipmate had a pet Burmese Python (I think) that he kept in a long wooden ammunition crate. Every Sunday, he would take it out for a feeding, which event usually passed for the highlight of our dreary existence for the week. A bunch of bored, bearded, half-dressed sailors would form a ring into the center of which someone would throw a live duck. The python would slowly slither over to the petrified fowl and then take an hour or so enveloping, crushing, and swallowing it. I still have pictures. As I recall, the guy who owned the giant snake had stenciled on the side of its wooden-crate home, in all-caps military-style lettering: "SNAKE, BIG FUCKING".

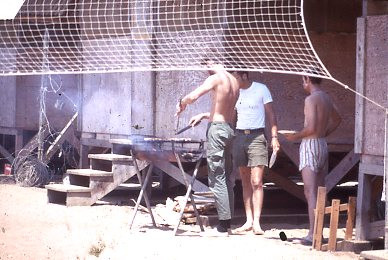

Sunday Barbeque after Volleyball Game

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

Narrative text pending.

More Sunday Barbeque festivities

[Photo by Mike Turner]

[Photo by Mike Turner]

Mike Turner and shipmates getting through another day-after-yesterday and day-before-tomorrow. As Mike wrote in a letter to me (which spoke for most of us, as well): "Most of my time at SA was repetitious. Work, sleep, drink. repeat. I didn't like being penned in on that base. No where to go. But, you can't get into too much trouble in a base with no roads and in the middle of no where."

Traveling USO Show -- without the miniskirted Go-Go girls

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

Narrative text pending.

The Captive -- and captivated -- Audience

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

Narrative text pending.

Movie Night on the Song Cua Lon River

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

Narrative text pending.

Cleaned up, highly motivated, and ready to go home after R-and-R to Taipei, Taiwan.

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

Back from my end-of-year (1971), one-week R-and-R trip to Taipei, Taiwan. The start of a brand new year and my last month in Vietnam. I fell in love with a beautiful Chinese lady who worked at the Bankok Hotel where some Australian "mates" had talked me into staying. To give myself an excuse to talk to her every day, I asked her to tell me where I might buy a book on Conversational Chinese. I got the book and started practicing on her right away. I asked her out for a dinner at a French restaurant on New Year's Eve 1971. She kept me standing in front of the Train station with my bouquet of flowers for an hour. Just when I had about given up, she arrived in a taxi. "I thought you were drunk," she told me, "but I thought I should come, just to make sure you really meant your invitation." Something like that. After an evening spent strolling around a nearby park after dinner, I told her that I would come back to Taipei next year in September as a college foreign exchange student. I asked for her address so I could write her until then. She didn't seem to believe me, but she gave me her address anyway. The next day, New Years, 1972, I returned to Vietnam to finish up my last month "in-country." Once back at Solid Anchor, I had this photo taken of me writing to her with the book on Conversational Chinese clearly visible in the foreground. I had a new goal in life that I swore nothing would prevent me from achieving. Love will do that to a surplus sailor.

Getting Short. Down to the final days at Solid Anchor and Vietnam (January, 1972).

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

I had finally gotten "short," but that last two weeks seemed to stretch out in front of me forever. I begged my supervising officer to let me go a week early, so that I could get back to Saigon with sufficient time to get through DEROS (Date of Expected Return from Overseas) processing. After all this time -- a year-and-a-half -- the thought of spending one more day in Vietnam seemed unimaginable. So I did my sentence down to the last moment before packing my seabag with my few remaining possessions: a camera, a tape recorder, and some Japanese language tapes, my helmet and flak jacket. I no loner had my M-16 rifle and ammunition, since I had lost them in the river one night during a mortar attack on the base. No need for them anyway, since I had no interest in shooting anyone. Then I went out to "Nam Can International Airport Terminal" at the base end of our prefabricated steel runway and sat waiting for the sound of the Air Force Carribou (C-7) to arrive for its weekly visit.

Last look at Nam Can International Airport Passenger Terminal

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

As I sat waiting for the Air Force to land and pick me up, I could hear the noise from the Carribou's engines grow louder as the plane approached. Because of the low cloud cover I couldn't see the plane but I heard it circling overhead. Then I heard the sound of the engines fade away as the plane flew back the way it had come. "What the hell just happened?" I demanded to know of the radioman on duty.

Stood up by the US Air Force

[Internet photo]

[Internet photo]

The Air Force Carribou scheduled to land and pick me up for my return trip home didn't want to come down and land due to a low cloud ceiling because this poor visibility would force them to come in on a long, low-altitude approach, making them an easy target for ground fire. So they just flew back to their home base and left me stewing and seething by the "Nam Can International" sandbag terminal.

Rescued by Air America.

[Internet photo]

[Internet photo]

Just my luck, though, an Air America mail delivery plane dropped in with some mail and the pilot asked: "Anybody need a lift?" I jumped in with my bags and had to sit on a plywood deck because the little plane had no seats for passengers. No problem. He flew me up to Binh Thuy Air Force Base where I hopped a ride on a bigger plane up to Saigon and then out of that miserable excuse for a "country." I've never had much use for the CIA (which everyone knew ran Air America as a front) because, normally, they "Can't Identify Anything" (like the address of the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade, which President Bill Clinton bombed using bad "intelligence" supplied by them). Nevertheless, on this one occasion they did just fine.

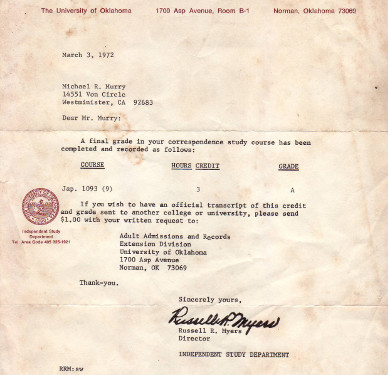

USAFI Correspondence Course in Japanese (University of Oklahoma) document of completion.

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

In March of 1972, a month after I returned from Vietnam and got out of Uncle Sam's Canoe Club (a.k.a., the United States Navy), I received in the mail a document confirming my completion of the USAFI correspondence course in Japanese that I had taken up as a "hobby" while at Solid Anchor after the drunken "Monsoon Escapade" that had almost landed me in a rubber room. Three college credits with a grade of "A" from the University of Oklahoma. I continued my study of Japanese over the years, with many far reaching consequences. But more on that history if time allows.

A Man of My Word - Back in Taiwan as Promised (September 1972 - December 1973)

[Photo by Michael R. Murry]

I left the southern part of Vietnam at the end of January 1972. Shortly thereafter, on February 2, I got my honorable discharge from the U.S. Navy and returned to Long Beach State College where I had completed one year before enlisting on August 6, 1966. I felt like an innocent man let out of prison who had committed no crime. I had promised the Chinese lady in Taipei that I would return in September of 1972 as a foreign exchange student, but to qualify for that program I had to complete several semesters worth of Chinese and Japanese languages in only one semester. This I did, while writing her letters several times a week demonstrating my growing command of written Chinese. She finally had to accept the fact that I meant business. I returned to Taipei, Taiwan, in early September, 1972, and studied there for another year-and-a-half before returning to the United States to work on my degree program. The lady and I got married at the Taipei City Courthouse in November of 1973. My new wife followed me back to the United States shortly once she had obtained all of her immigration papers. In those days, it didn't take that long and she had her Green Card waiting for her when she cleared customs in Hawaii, her port of entry before continuing on to California to join me. As if decreed by Fate, if I hadn't extended my tour in Vietnam, I wouldn't have taken that R-and-R to Taipei, and then any number of other fortuitous consequences would possibly not have happened for me. But more about that some other time ...

An Xuyen Province

Republic of Vietnam

Nov. 1970 - Jan. 1972

![]()

Combat Action Ribbon

Awarded Mar. 23, 1971

Links

- Larry Johnson

- Patrick Armstrong - Russia Observer

- Gilbert Doctorow

- Reminiscence of the Future

- Scheerpost

- The Jimmy Dore Show

- Consortium News

- Counterpunch

- Common Dreams

- Anti-War

- space.com

- TomDispatch

- Bewildering Stories

- The Unz Review

- Information Clearing House

- The Vineyard of the Saker ⟶ blog frozen

- Russia Today

- Club Orlov

- Moon of Alabama

- The Duran

- The Real News Network

- Caitlin Johnstone - Australian Journalist/artist

- Sputnik News

- Bracing Views

- The Grayzone